Trapped in an Ever-Growing Web

- Oct 11, 2020

- 4 min read

Updated: May 9, 2021

Humble Beginnings

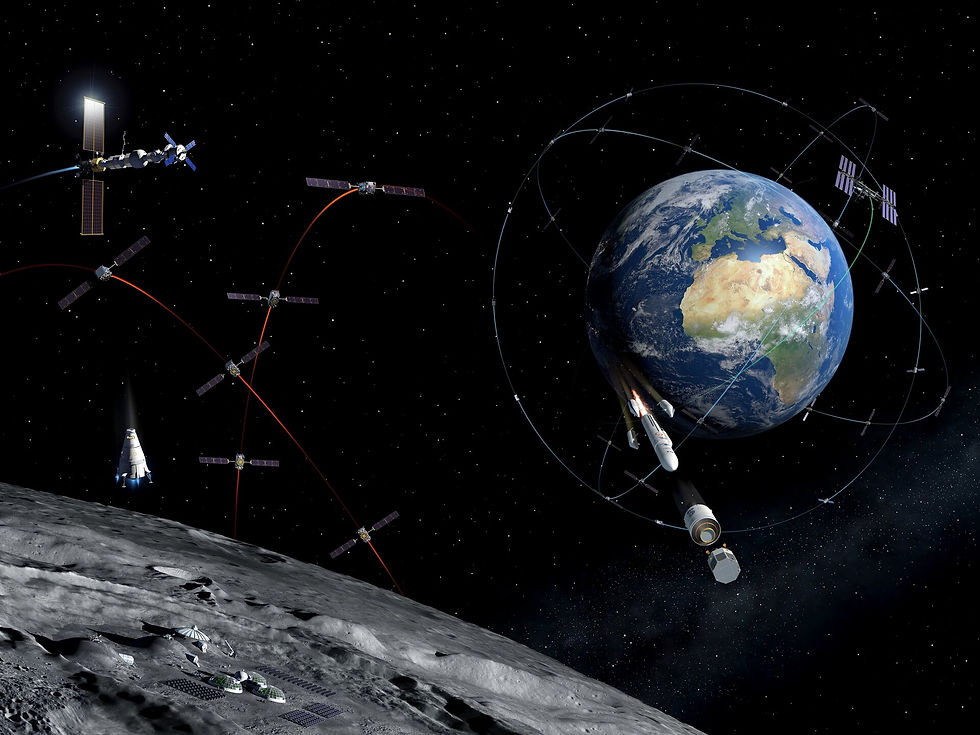

From the first satellite, Sputnik 1 [1] (from Спутник, once meaning ‘fellow traveller’, now meaning ‘satellite’), launched in 1957 by the Soviet Union [2], we as a species have continued to develop and innovate our technology to better suit our needs in every day life.

Since then, many more have been launched, leading to 2,666 to be in orbit around Earth (as of 1st April 2020) [3], with many more having crashed into Earth or made into debris.

Littering… in Outer Space

This debris has built up over the 63 years satellites have been launched into space. As of July 2009, there are ~19,000 of these measuring greater than 10cm [4]. This may not sound big, but when travelling at hypervelocity (4-5km/s [5]), they can really do some damage, leading to geostationary satellites (satellites over one location on Earth) using 5-10% of their total cost on design (to mitigate against damage from impact), tracking debris and replacing satellites if they get severely damaged.

As this amount builds up and up, this could bring about the ‘Kessler syndrome’: a cascade of collisions, brining about more and more self-generating collisions, stopping some orbits from being used because of this [6].

This then makes it harder and harder for satellites to be launched and stay safe in orbit, for use in the longer term.

Hypervelocity Impact. Credit ESA, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

Calling from Afar

However bad this has been for our planet, one thing is for sure: our lives wouldn’t be the same without them. From the TV and mobile phones, to GPS and weather monitoring, and even monitoring how the climate is changing over a long period of time [7], satellites have been invaluable to us, and many can’t imagine what life would be like without them.

They make sure our lives are interconnected, even across great distances, whilst helping us stay safe, even keeping track of the most remote events, like that of the Nepal earthquake of 2015, letting aid arrive quickly, meaning less people die, even in countries that seem so isolated, like Nepal [8].

‘Flarewell’

Iridium Communications (2018) [9]

They may be fantastic things, but, as every protagonist in a good story does, they have one fatal flaw, specifically for us here on the ground: they reflect light. Indeed, they reflect light so much that, in recent years, people have come out in their droves to see the spectacle of satellite flares, like that of the iridium satellites (having recently been decommissioned to be replaced by less reflective satellites), which created bright flares in the sky from reflecting sunlight at the Earth [9].

However fun flares from satellites seem, one thing is for sure: they are the best photo-bombers when it comes to astrophotography and general astronomical observations.

So, with the realisation of this flaw and its impacts on modern science, you would think people would realise it would be a bad idea to put too many more up, since the sky is bad as it is with all those satellites up there already.

Comet Holmes and Iridium Flare. Credit: Brocken Inaglory, CC BY-SA 3.0

A Net Across the Sky

The answer is, of course, no. This is due to the new Starlink satellites. Like the Iridium satellites, they are communications satellites in orbit around Earth, for fast communications around the world. However, they are slightly different, in the way that they are more compact, provide internet access across Earth, and there are a lot more of them. In fact, there are over 626 more satellites orbiting (the most recent ones deployed on 6th October 2020 [14]) at present [10] [11].

I think anyone hearing that will think that it has got to have some impact on the sky, and it does. It creates a “train” of satellites in the sky, visible with the naked eye [12]. Starlink are going to change this though, with less reflective coatings on the satellites, making them half as bright, but this isn’t going to stop the disruption to the professional observer or scientist looking for a good shot [12], now even striking fear into radio astronomers, with “satellite transmissions leading to a 70% loss in sensitivity in the downlink band” [13]

They are, however, going to provide an important service, providing Internet to those with none, or with a bad connection, helping increase development and quality of life, but at what cost to our view of the night sky? [13]

Starlink Satellites across Blanco 4-metre Telescope.

Credit: NSF/CTIO/AURA/DELVE, CC BY 4.0

Outer Space: A Global Commons

The UN classifies outer space as a global commons [14], but for how long will we all be able to use it freely, before it is blocked off for those who wish to see it? This exponential growth in satellites may free the world up to us on Earth, but at what cost to that basic human right of the night sky?

By George Abraham, ADAS member

Click here for the previous news article

Click here for the next news article

Click here for a great video by Richard Bullock showing a timelapse of the Starlink constellation.

References

"What is a Satellite?" NASA. Archived from the original on 11th October 2020.

"Sputnik 1". NASA. Archived from the original on 11th October 2020.

"How many Satellites Orbit Earth". Geospatial World. Archived from the original on 11th October 2020.

"Space Debris". Earth Observatory. Archived from the original on 11th October 2020.

"What are Hypervelocity Impacts?" ESA. Archived from the original on 11th October 2020.

"What are Satellites Used For?" UCS. Archived from the original on 11th October 2020.

"The Cost of Space Debris". ESA. Archived from the original on 11th October 2020.

"Nepal Earthquake: Hundreds Die, Many Feared Trapped". BBC News. Archived from original on 11th October 2020.

"Join Us to Say #flarewell to Iridium Flares". Iridium. Archived from the original on 11th October 2020.

"Starlink". Starlink. Archived from the original on 11th October 2020.

"How a New Satellite Constellation Could Allow Us to Track Planes All Over the Globe". The Verge. Archived from the original on 11th October 2020.

"Starlink Already Threatens Optical Astronomy. Now, Radio Astronomers are Worried". Science Magazine. Archived from the original on 11th October 2020.

"How to See a 'Starlink Train' from you Home this Week as SpaceX Satellites Swarm the Night Sky". Forbes. Archived from the original on 11th October 2020.

"SpaceX's Darker Starlink Satellites are still Ruining Astronomers' Research". Futurism. Archived from the original on 11th October 2020.

"How Africa can Tap into SpaceX's Starlink Satellites". IT Web. Archived from the Original on 11th October 2020.

Comments